I thought i share with you this article to show what really takes place behind the scenes of the fruit and vegetables markets that are not ethic/organic certificated…I always buy my foods at shops that offer organic and ethic quality, it may cost a little more but i know i am respecting all those that participate in bringing these foods on my table and one can truly feel the taste of these foods as when something is produced with love and care it reflects that and when it is not like in the conditions described here, well the energy is something else. Always buy organic and ethic ,even if you must eat less.

Namaste

Nikos

The shops along the main road of Lappa, a small village in the northwestern Peloponnese, differ from the shops you’d find in other provincial areas in Greece. The signs on the few shops − cafes, souvlaki joints, bakeries − written in Greek, intermingle with other shop signs that are written in Bengali.

There’s a restaurant serving Bangladeshi food and a clothing shop. There’s a mini market where you can find everything from groceries to mats, blankets, fans, next to packaged products, all of which are made in Bangladesh. The shop owners, who are from Bangladesh, are well aware of the needs of their consumers: the community of thousands of their fellow migrant land workers, who live in the area and work in the strawberry fields.

Sometimes, they meet these consumer needs in imaginative ways, combining various products and services. The clothing store also sells tools and spare parts. Inside the mini market, a separate area has recently been created behind a wooden structure – a barber shop. A haircut costs €5 and a shave is €2, thus providing the owner with an additional income. “When I told my accountant what I wanted to do, he laughed, but he told me it was possible,” he says.

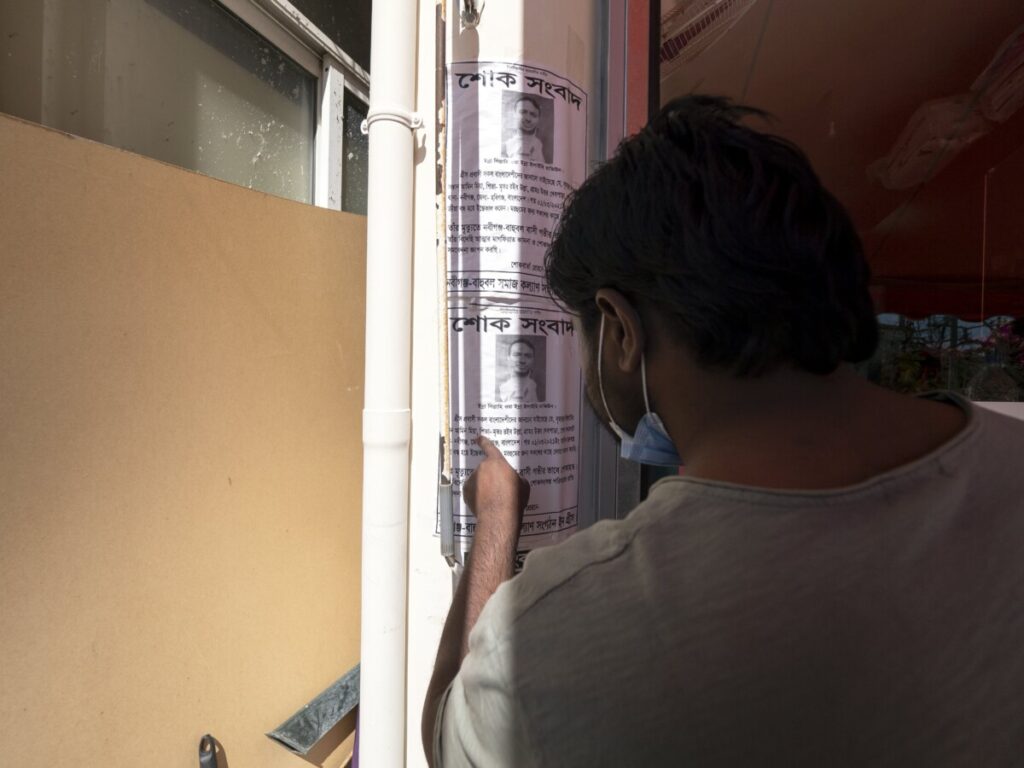

Two death announcements in Bengali

Three men sit in plastic chairs in front of the shop. One watches a cartoon on his phone, another sips an energy drink with a straw. Next to them, on a pole next to the shop front, two death announcements in Bengali have been posted.

The first one says that Odan Mahmad Rajun committed suicide on March 21, 2021. The second one announces that twenty days earlier, Amin Mia (amin means beloved) died of a heart attack. Amin Mia had recently come to Greece to work, like all of his compatriots. And like most of his compatriots, he was undocumented.

It is estimated that four to five Bangladeshis die here every year. Each time, members of the community and the embassy in Athens organize the repatriation of the bodies − a journey of more than 6,500 kilometers.

The “distortion” of the population in Manolada

There are people, in all regions of Greece, who fear that local populations will become “distorted” by the arrival of refugees and immigrants. There is one area, however, where this “distortion” has already occurred, but it is a welcome change and for years it has become a necessary one. This area is Manolada.

“Manolada” refers to the broader area in the prefecture of Ilia in the Peloponnese, about 40 kilometers west of Patras, which includes the villages of Manolada, Nea Manolada, Neo Vouprasio, Lappa, and Varda. The most recent census in Greece took place in 2011. At that time, Manolada had a population of 844, Lappas 1,000, and Neo Vouprasio 128. But the actual number of people living in the area is much higher.

As we drive along the road that connects the villages, we arrive at Nea Manolada. Although it’s Sunday morning, there’s not much traffic at the church in the center of the village, rather all the activity is outside the neighboring betting shop, where a group of men of Indian descent are gathered, with betting slips in their hands.

Next to the Greek shops, the abandoned village houses and the two-story dwellings with large yards – a community has developed, people who live in dilapidated farmhouses and makeshift camps, well-hidden from the main streets.

They mostly live without papers, undocumented, invisible to the Greek state. Like Ali.

Manolada’s “red gold”

Although his soft voice, facial features and body type suggest that he may be much younger, Ali tells Solomon that he’s 17 years old. In 2004, when Ali was born, strawberries in Manolada were among the many products cultivated in the area and there were 1,200 stremmata (approx. 300 acres) of strawberry fields.

The reason the teenager from Bangladesh and up to 10,000 migrant workers have come to the area is that in past decades, strawberry production has increased rapidly. In 2012 covered 12,000 stremmata (approx. 3,000 acres) and is currently estimated to have exceeded 15,000 stremmata (approx. 3,750 acres).

Manolada cultivates more than 90% of the total strawberry production in Greece, which is almost entirely available for export. In a recent report, one of the major producers in the region, Giannis Arvanitakis, refers to an “exclusively exportable product” adding that “only 4% of production” is slated for the Greek market.

“Red gold” – the term coined by the Greek prime minister at the time, George Papandreou − refers to an industry worth tens of millions of euros which is constantly growing. According to the Union of Fruit & Produce Exporters, every year the region’s strawberry exports break the record of the previous year.

In 2020, despite the pandemic, when producers were forced to discard part of their product, as it could not be exported, strawberry exports generated 54,967 tons (worth €71.7 million), which was an increase from 2019, at 45,178 tons (€55.4 million).

In 2021, production and exports are expected to exceed that of the previous year. And producers estimate that by 2025, strawberry fields in the area will cover 25,000 stremmata (approx. 6,200 acres).

Greek strawberries by Bangladeshi workers

It is estimated that the integral reason for the success of the strawberry industry is the dam on the Pineios River, which makes the soil of Manolada so fertile. Another key component is the cheap labor.

Until about 15 years ago, in Manolada, the labor force consisted of Albanian, Romanian, Bulgarian and Egyptian land workers. Since then, while a small number of mostly Bulgarians and Romanians still arrive at the beginning of each season, the vast majority of land workers are Bangladeshis and to a lesser extent, Pakistanis.https://www.youtube.com/embed/r_vOOCp_WnQ?feature=oembed

The relationship that has been established between the strawberry production and the labor force that ensures it, has become so well-connected that the majority of Bangladeshi land workers in Manolada come from the same city, Sylhet, which is located in northeastern Bangladesh.

In recent years, Solomon has visited Manolada several times, and has covered, among other topics, the challenges that thousands of land workers faced during the pandemic.

During our visits, we discovered the existence of “second generation” land workers. For example, young men who came to Manolada to join their fathers who have been working in the region for years, or cases like Ali who came to find his uncle, after he told him that “there’s work to be found here” (but Ali didn’t meet him after all, as the uncle moved on to Italy).

Bangladeshis are much cheaper than their Balkan predecessors, as they are content with a daily wage of €24 for a seven-hour workday, compared to €35-€40 for other nationalities.

In addition, their body type and relatively short height are considered ideal for both sowing and harvesting strawberries. Moreover, another factor is their mild temperament and status in the country: they are considered “quiet” and they “don’t create problems”. As most are undocumented, their fear of being deported or arrested causes them to not react as a community.

The strawberry industry employs both highly skilled land workers, who may have more than ten years of experience, as well as newcomers who head to Manolada as soon as they cross the border. The season starts at the end of September and ends in late June. At its peak, after December, it is estimated that up to 9,000 land workers, work six days a week in the greenhouses. The housing conditions in which most of them live are no different than the greenhouses where they work.

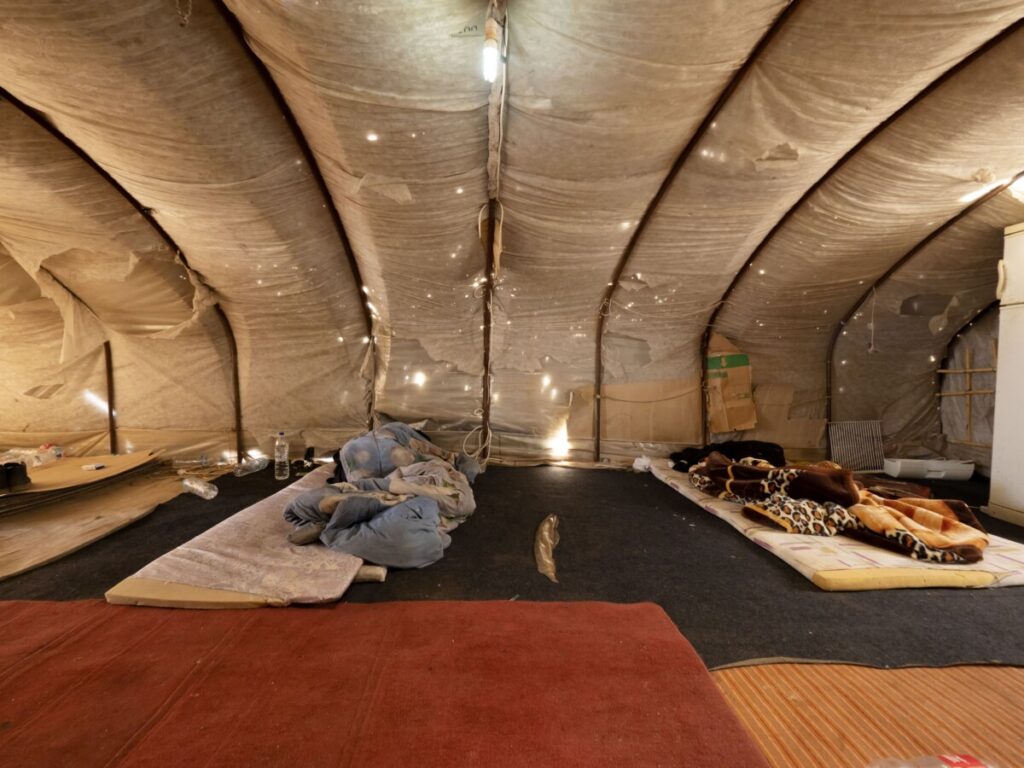

The camps of Manolada

The camps are scattered among vast strawberry fields. They consist of about a dozen makeshift shelters constructed using reeds for the base and frame. The “walls” are made with the same plastic sheets (used for the greenhouses), reinforced with blankets.

Bangladeshi land workers speak little Greek, only what they’ve learned through work. However, they’ve learned the Greek word that describes where they live: parāges or “shacks”.

In the camp we visited, more than 100 people were living in dozens of makeshift shelters. Most sleep on pallets, in two rows on either side of the space. With so many people living in such a small space, it is impossible to follow social distancing rules. In the spring, the heat inside the shacks is stifling, and the fans which are constantly working, are run on makeshift connections to power sources.

In most parts of the camp, the smell is also suffocating, as the toilet is simply a hole in the ground. There is no running water and those who live in the camp must wash outdoors; thus in winter they are often sick, and if unable to work, they don’t receive their daily wages.

Two stalls act as kitchens and there are four water tanks sheltered under a canopy. There’s a makeshift mosque, where some of the workers go each afternoon after work, in clean clothes, to pray.

The necessary system of “masturs”

Kasef has been in Greece for a year. He crossed the Greek-Turkish border at the Evros River, and as he traveled inland, he was caught by the authorities and detained for 15 days at a police station. He was then held for three months in Drama, at the Pre-Removal Detention Center of Paranesti.

He has received a letter urging him to leave the country within a month and has applied for asylum. Kasef says he has been wearing the same pants since he arrived in the country and complains that because he is Pakistani, he receives less pay than the others.

“There is very little work,” he says. If Kasef was in Greece a few decades ago, he would’ve spent his days wandering the fields asking for work. If he was in a northern European country, he might have turned to an employment agency.

But not in Manolada. Here, land workers don’t have a strong tie to their employers − they often don’t even know their employer’s full name, perhaps only their first name, if it’s even their actual name. Land workers in Manolada rather build relationships with the masturs, who act as mediators between workers and producers, and in the camps where the workers live.

The masturs or commanda are their compatriots. Usually, they’re people who’ve been living in Manolada for years, who started out as land workers, can speak some Greek, and have gained the trust of the producers. They no longer work in the fields. During the day, they can be found at the village mini-markets sipping energy drinks or ordering supplies for the camp, which are purchased on credit and always paid in full at the end of each month.

“It just can’t be done without the mastur“

The masturs maintain close ties with local producers. When the season is over, they don’t travel to other areas like the other workers, but they remain in Manolada to help with other work.

A small producer in the area, who agreed to speak to Solomon on the condition of anonymity, stated that the mastur is crucial for the operation of the industry, “without the mastur it just can’t be done,” he said.

He employs about 20 land workers in his fields, he explained, and he can recognize about half of them. He only knows a few of their names. And he is unable to coordinate and communicate with them on his own. He simply tells the mastur how many people he needs, and the mastur takes care of the rest – he goes to the camp and gathers the needed workers.

The mastur is given all of the workers’ wages and at the end of the month he distributes the money to them, keeping €1 per day of the €24 per day which each person receives. However, in recent years some mastur in Manolada ask their compatriots for €100-€200 at the beginning of the season to find them a job, causing their indignation.

It is extremely rare for land workers living in the same camp to work for the same employer. During the season, depending on the needs and the available daily wages, they can be employed by more than one producer − always through the mediation of the mastur.

€40 rent for a plastic tent

The land workers are obliged to pay €30-€40 per month in rent to the mastur, money that usually goes to the owner of the field. However, when we told the small producer who spoke to us that every migrant living in the camp on his field is paying rent every month, he replied that he has not received any payment for this.

“Let them just give me money to cover the electricity bill and I don’t want anything else,” he said.

For the owners of fields, where up to 100 people are housed in camps, there is a tax-free monthly income of €3,000. We visited a farm house where there were a total of 65 people living in a shared common space. The residents there pay €30-€40 each per month − a total of about €2,000 per month for living in horrible conditions.

The shooting incident in 2013

The living and working conditions in the area first became widely known in 2007, when a fire in a camp broke out, exposing the crudely-built structures. But the event that brought international attention to the situation in Manolada occurred in 2013.

In April of that year, about 150 Bangladeshi workers, who were employed in the strawberry fields, went on strike and demanded they be paid their back wages. Their employer, Nikos Vangelatos, who had been in the area for a few years but owned a significant percentage of the total production through contract farming, refused to pay them.

When an attempt was made by the employer to hire other land workers to replace them, 150 of the unpaid migrant workers gathered to protest. Their supervisors initially fled, only to return with shotguns. One of the supervisors opened fire, injuring 30 Bangladeshis.

The incident made international headlines, and reports described the industry in Manolada as “blood strawberries”. An international boycott followed. Since then, the strawberries cultivated in the area are no longer promoted as being from “Manolada” (which used to be a mark of a quality product) but rather from “Ilia” (the prefecture where Manolada is located).

The absence of the state

On April 30, 2013, in the aftermath of the attack on land workers, the Regional Council of Western Greece met. After condemning the incident and calling for an investigation of the responsible state authorities, Deputy Regional Head of the Ilia Prefecture, Haralambos Kafiras referred to these “three essential conditions for restoring law and human dignity to the region”:

- issuing proper documentation to immigrants, so they can live and work legally

- developing safe and hygienic living conditions

- protecting the workers’ labor and individual rights

Vassilis Kerasiotis is the lawyer who represented the injured land workers. In 2017, the case was heard in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), and the accused supervisor was condemned, in 2019, to a reduced sentence of eight years imprisonment, which can be paid off at €5 per day.

Kerasiotis still maintains strong ties with the region. We asked him if he thinks things have changed in terms of the three essential conditions, in the eight years since the incident occurred.

“These three essential conditions are interrelated. Clearly, the main issue is to regulate their employment status, in a framework of legal seasonal migrant land workers. The rights of legal immigrants are more easily protected than those who are undocumented,” he told Solomon.

“However, this will create a more transparent system, without using mediators in the recruitment of land workers needed for agricultural production.”

“Unlawfulness” by the state

Following the decision of the ECHR, which issued a judgement against Greece for violation of the prohibition of human trafficking and forced labor in the agricultural sector, the Greek state was obliged to comply and ensure decent living conditions for the thousands of migrant land workers.

In order to comply with the ruling of the ECHR, the government created Article 13A of Law 4251/2014, a provision that Apostolos Kapsalis, (a researcher at the Institute of Labor, established by the General Federation of Greek Workers), calls “unlawful”.

Article 13A of Law 4251/2014 includes provisions regarding the “employment of illegally residing third-country nationals in the agricultural sector”, who are allowed to work legally and be insured via worker’s checks.

However, as Apostolos Kapsalis explains to Solomon, “the only way for an immigrant to work under Article 13A and be insured using a worker’s check, is to be ‘deportable’. If he isn’t, he must receive a deportation order against him.”

What does this mean in practice?

“For example,” Kapsalis explains, “someone is in the country illegally. An employer wants to hire him, so the immigrant gets a deportation order against him from the police station. But a suspension of deportation is issued because the employer hires him to work for six months under Article 13A. However, after six months, as soon as his job is completed, the immigrant still has a deportation order pending against him.”

The paradox created by Article 13A is that, until then, the immigrant did not have a pending deportation order which he was forced to obtain in order to be able to work legally for six months.

“Although Article 13A was supposedly introduced in the context of combating forced labor, what remains is still a form of obligation and absolute dependence of the employee on the employer,” says Kapsalis.

A payroll expense or fertilizer?

Certainly it’s in the interest of the workers to be employed and insured via a worker’s check, and it’s no different for the producers.

Since 2015, when the tax code was changed, the expenses related to the payroll of land workers were deducted from a producer’s taxes. Rarely, however, are there enough land workers who can work legally, with credible sources estimating that only one in twenty workers in the greater Manolada region are employed with insurance.

What’s most common is that documented Bangladeshi workers are insured using a worker’s check and also receive the salaries of additional workers, collecting thousands of euros in their account, which they then distribute to their fellow workers.

“They themselves don’t work, that’s their job, but one day the tax office will catch up with them,” said the small producer. He added that not establishing a framework so that land workers can be employed legally has various consequences – tax evasion, lost revenue for insurance funds − and that every year his accountant is forced to seek a solution for his payroll expenses.

In 2020, an investigation by Lighthouse Report in collaboration with Der Spiegel, Mediapart and Euronews, shed light on how producers in the region listed their payroll expenses as “fertilizer” on their annual balance sheets.

According to the balance sheets of the largest producers in the region, on paper, producers appeared to have employed only about six to ten people for each field. But consistent with the workers and given the size of the land, several hundred workers are needed to cultivate each field.

The Convention that was never ratified

One might think that the state should intervene in the case of Manolada, but the truth is that the state, (in addition to a peculiar tolerance for the continuation of the terrible living and working conditions in the region), lacks the legal framework that would actually give it the ability to act.

Although Greece is a country with a large agricultural industry, the state has not created specialized legislation for carrying out labor inspections in agricultural regions.

In 1955, Greece ratified the International Labour Organization’s 81st Labour Inspection Convention on “labour inspection in industry and commerce” and effectively used this to establish and operate the Body of Labor Inspectors (ΣΕΠΕ) in Greece.

However, since 1969, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has recognized that the inspection of the agricultural sector has its own specific features and requirements, and in general has separated the industry from the inspection of the workplace, with a Convention signed in June 1969 in Geneva.

The ILO’s 129th Labour Inspection Convention on “labour inspection in agriculture” provides the overall framework with 35 articles, which stipulate that each country that ratifies the Convention should have a system of labor inspection in agriculture, which will operate under a special department of labor inspectors-civil servants, whose main task will be to inspect working conditions in the agricultural sector.

However, currently Greece has still not ratified the 129th Convention which offers the necessary legal arsenal to combat labor exploitation issues in the agricultural sector. Thus, to date, inspections have not been carried out in the fields, but mainly indoors (packing plants), because the 81st Convention (which Greece has ratified) stipulates that inspections should be carried out in covered areas.

The two previous governments had expressed their intention to ratify the 129th Convention. On July 14, 2017, the Minister of Labor at the time, Efi Achtsioglou, stated that “we are entering the final stages for the completion of the procedures for the inspection of agricultural regions. The unclear legislation and inaction that allowed and tolerated Manolada-type situations is over.” However, four years later, and the 129th Convention has still not been ratified.

It’s either Manolada or a detention center

For the majority of Bangladeshis in Manolada, the reality is very different in relation to what the traffickers had promised them before they arrived in Greece: most still lack the papers they were promised, the wages are significantly lower, and many intend only to stay here until they decide what their next step will be.

Often, those who get papers leave the area; some open their own shop in a city or work as dishwashers in restaurants. However, until they get their papers, in the meantime they prefer to remain here, where they know that the police − who are tolerant of the workers who ensure the region’s production of “red gold” − will not bother them.

They may not know much about Greece, but they know that if they are caught by police somewhere outside of the Manolada area, they may end up in a Pre-Departure Detention Center and they know they could be held there for up to 18 months.

The 65 Bangladeshis we met who were sharing the small farmhouse, showed us videos on their phones of such a detention center in Corinth, of the uprising that followed the suicide of a Kurdish detainee last March.

In the video, young men can be seen shouting at the guards, from behind the barbed wire that restricts their lives for endless months.

The Bangladeshis tell us, “No, it’s better here.”

The article is published in the context of Solomon’s in-depth series of reports on “Migrant workers in Greece in the time of COVID-19 ″ and is supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Office in Greece.

Greek strawberries “made in Bangladesh” – Solomon (wearesolomon.com)

Like this:

Like Loading...

JUNE 20, 2021

JUNE 20, 2021